Pre-history

Archaeologists have found evidence that the Lviv area was inhabited during the 5th century. This fact places this settlement within the territory of once powerful state of White Chroatia. In the 9th century, a Lendian settlement existed in the area that is now Lviv, between Castle Hill and Poltva river. Lendians are a West Slavic tribe. In the 10th century, the Lendians built a fortified settlement on Castle Hill. In 981, the towns in current south-eastern Poland and western Ukraine, the ‘Cherven Towns’, were conquered by Vladimir I and came under the rule of Kievan Rus. In 1977 they discovered that the Orthodox church of Saint Nicholas had been built on an old cemetery.

Halych-Volyn Principality

Lviv was founded by King Danylo of Galicia in the Ruthenian principality of Halych-Volhynia and named in honour of his son Lev. In 1261 the town was invaded by the Tatars. Various sources relate the events ranging from destruction of the castle to a complete destruction of the town. But all sources agree that it was on the orders of the Mongol general Burundai. The ‘Naukove tovarystvo im. Shevchenka’ of the Shevchenko Scientific Society, say that the order to raze the city was reduced by Burundai; the Galician-Volhynian chronicle states that in 1261 “Said Buronda to Vasylko: ‘Since you are at peace with me then raze all your castles.'” Basil Dmytryshyn states that the order was implied to be the fortifications as a whole “If you wish to have peace with me, then destroy [all fortifications of] your towns.” According to the Universal-Lexicon der Gegenwart und Vergangenheit the town’s founder was ordered to destroy the town himself.

After Knyaz (King or Prince) Daniel’s death, Knyaz Lev rebuilt the Lviv around the year 1270 at its present location, choosing it as his residence and making it the capital of Galicia-Volhynia. The city is first mentioned in the Halych-Volhynian Chronicle regarding the events that were dated 1256. The town grew quickly due to an influx of Polish people from Kraków, Poland, after they had suffered a widespread famine there.

Around 1280 Armenians lived in Galicia and were mainly based in Lviv, where they had their own Archbishop. The town was inherited by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania in 1340 and ruled by voivode Dmitri Detko, the favourite of the Lithuanian prince Lubart, until 1349.

Galicia–Volhynia Wars

During the wars over the succession of Galicia-Volhynia Principality in 1339, King Casimir III of Poland undertook an expedition and conquered Lviv in 1340 and he burned the old princely castle down. Only Saint Nicholas’ church remains from this time period. Poland ultimately gained control over Lviv and the surrounding region in 1349. From then on, the population was subjected to attempts of Polonizing and Catholicizing them.

Casimir built two new castles. In 1356 he brought in more Germans and within 7 years he granted the Magdeburg rights to the city, that implied that all city matters were to be resolved by a council elected by the wealthy citizens. The city council seal of the 14th century stated: S(igillum): Civitatis Lembvrgensis.

After Casimir died in 1370, he was succeeded as king of Poland by his nephew, King Louis I of Hungary, who put Lviv together with the region of Galicia-Volhynia in 1372, under the administration of his relative Władysław, Duke of Opole. When Władysław retreated from his post in 1387, Galicia-Volhynia became occupied by the Hungarians. But soon Jadwiga, the youngest daughter of Louis, also ruler of Poland and wife of King of Poland Władysław II Jagiełło, unified it directly with the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland.

Kingdom of Poland

As part of the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland, Lviv (Polish: Lwów) became the capital of the Ruthenian Voivodeship that was founded in 1389. Before that happened, King Casimir III the Great granted the city Magdeburg rights on 17 April 1356. The city’s prosperity during the following centuries is owed to trade privileges granted by Casimir, Queen Jadwiga and the subsequent Polish monarchs.

The city became the seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese in 1412, which had been in Halych since 1375. First Catholic Archibshop, who resided in Lviv, was Jan Rzeszowski. The city was granted with the staple right in 1444, which resulted in its growing prosperity and wealth, as it became one of major trading centres on the merchant routes between Central Europe and Black Sea region. It was also transformed into one of the main fortresses of the kingdom, and was a royal city, like Kraków or Gdańsk. In the 17th century, Lviv was the second largest city of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, with a population of 30,000.

In 1572, one of the first publishers of books in current Ukraine, Ivan Fedorov, a graduate of the University of Kraków, settled here for a brief period. The city became a significant centre for Eastern Orthodoxy with the establishment of an Orthodox brotherhood, a Greek-Slavonic school and a printer who published the first full versions of the Bible in Church Slavonic in 1580. A Jesuit Collegium was founded in 1608, and on 20 January 1661 King John II Casimir of Poland issued a decree granting it “the honour of the academy and the title of the university.”

The 17th century brought invading armies of Swedes, Hungarians, Turks, Russians and Cossacks to its gates. In 1648, an army of Cossacks and Crimean Tatars besieged the town. They captured the High Castle, murdering its defenders, but the city itself was not sacked, because the leader of the revolution, Bohdan Khmelnytsky, accepted a ransom of 250,000 ducats and the Cossacks marched northwest towards Zamość. It was one of two major cities in Poland that was not captured during the so-called Deluge. The other one was Gdańsk (Danzig). At that time, Lviv witnessed a historic scene, as King John II Casimir made his famous Lwów Oath. Two years later, John Casimir declared Lviv equal to two historic capitals of the Commonwealth, Kraków and Wilno, in honour of bravery of Lviv’s residents. In the same year, 1658, Pope Alexander VII declared the city to be ‘Semper fidelis’, in recognition of the its key role in defending Europe and Roman-Catholicism from the Muslim invasion.

In 1672 it was surrounded by the Ottomans who also failed to conquer it. Three years later, the Battle of Lwów (1675) took place near the city. Lviv was captured for the first time by a foreign army since the Middle Ages in 1704, when Swedish troops under King Charles XII entered the city after a short siege. The plague of the early 18th century caused the death of approximately 40% of the city’s population (about 10,000 people).

Habsburg Empire

In 1772, following the First Partition of Poland, the region was annexed by Austria. Known in German as Lemberg, the city became the capital of the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria. Lviv grew dramatically under Austrian rule, increasing in population from approximately 30,000 in 1772 to 206,100 by 1910. In the late 18th and early 19th century, a large influx of Austrians and German-speaking Czech bureaucrats gave the city a quite Austrian character by its orderliness and by the appearance and popularity of Austrian coffeehouses.

In 1773, the first newspaper in Lviv, the Gazette de Leopoli, was published. In 1784, a German language University was opened, which closed in 1805 and was opened again in 1817. German became the academic language.

In the 19th century, the Austrian administration attempted to Germanise the city’s educational and governmental institutions. Many cultural organizations which were not pro-German, were closed. After the revolution of 1848, the academic language at the University shifted from German to include Ukrainian and Polish. Around that time, a certain sociolect developed in the city known as the Lwów dialect. Considered to be a type of Polish dialect, it had its roots in other languages besides Polish. In 1853, it was the first European city to have street lights because of innovations by Lviv’s Ignacy Łukasiewicz and Jan Zeh. In that year kerosene lamps were introduced as street lights, which were updated to gas lights in 1858 and to electrical lighting in 1900.

After the so-called ‘Ausgleich’ of February 1867, the Austrian Empire was reformed into dualist Austria-Hungary and a slow yet steady process of liberalization from Austrian rule in Galicia started. From 1873, Galicia was de facto an autonomous province of Austria-Hungary, with Polish and Ukrainian -or Ruthenian- as official languages. Germanisation was halted and the censorship was lifted as well. Galicia was subject to the Austrian part of the Dual Monarchy, but the Galician Sejm and provincial administration, both established in Lviv, had extensive privileges and prerogatives, especially in education, culture and local affairs. Lviv started to grow rapidly, becoming the 4th largest city in Austria-Hungary, according to the census of 1910. Many Belle Époque public edifices and tenement houses were erected. The buildings from the Austrian period, such as the Lviv Theatre of Opera and Ballet built in the Viennese neo-Renaissance style, still dominate and characterize much of the city’s centre.

During Habsburg rule, Lviv became one of the most important Polish, Ukrainian and Jewish cultural centres. According to the Austrian census of 1910, that listed religion and language, 51% of the city’s population were Roman Catholics, 28% were Jews, and 19% belonged to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. Linguistically, 86% of the city’s population used the Polish language and 11% preferred Ukrainian. At that time, Lviv was home to a number of renowned Polish language institutions, such as:

- the Ossolineum, with the second largest collection of Polish books in the world,

- the Polish Academy of Arts,

- the National Museum (since 1908),

- Historical Museum of the City of Lwów (since 1891),

- the Polish Historical Society,

- Lwów University, with Polish as official language since 1882,

- Lwów Scientific Society,

- Lwów Art Gallery,

- the Polish Theatre,

- Polish Archdiocese.

Lemberg (Lviv) in 1915

Lviv was the centre of a number of Polish independence organizations. In June 1908, Józef Piłsudski, Władysław Sikorski and Kazimierz Sosnkowski founded the Union of Active Struggle. Two years later, the paramilitary organization, called Riflemen’s Association, was also founded by Polish activists.

At the same time, Lviv became the city where famous Ukrainian writers (like Ivan Franko, Panteleimon Kulish, and Ivan Nechuy-Levytsky) published their work. It was a center of Ukrainian cultural revival. The city also housed the largest and most influential Ukrainian institutions in the world, including the Prosvita society dedicated to spreading literacy in the Ukrainian language, the Shevchenko Scientific Society and the Dniester Insurance Company, and it was also the base of the Ukrainian cooperative movement and served as the seat of the Ukrainian Catholic Church. Lviv was also a major centre of the Jewish culture, in particular of the Yiddish language, and was the home of the world’s first Yiddish-language daily newspaper, the Lemberger Togblat, established in 1904.

In the Battle of Galicia at the early stages of World War I, Lviv was captured by the Russian army in September 1914, but it was retaken by Austria–Hungary in June the following year. Lviv and its population therefore suffered greatly during the World War, as many of the offensives were fought across the territory around Lviv, causing significant collateral damage and disruption.

Polish-Ukrainian War

After the collapse of the Habsburg Monarchy at the end of World War I, Lviv became a battle arena where the local Polish population and the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen fought each other. Both nations perceived the city as an integral part of their new states, which at that time were forming in the former Austrian territories. In the night of 31 October – 1 November 1918, the Western Ukrainian National Republic was proclaimed with Lviv as its capital. 2,300 Ukrainian soldiers from the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen (Sichovi Striltsi), that had previously been a corps in the Austrian Army, took control over Lviv. The city’s Polish majority opposed the Ukrainian declaration and began to fight against the Ukrainian troops. During this combat an important role was played by young Polish city defenders, called ‘Lwów Eaglets’.

The Ukrainian forces withdrew outside Lwów’s confines by 21 November 1918. Elements of Polish soldiery began to loot and burn much of the Jewish and Ukrainian quarters in the city, killing approximately 340 civilians. The retreating Ukrainian forces besieged the city. The Sich riflemen reformed into the Ukrainian Galician Army (UHA). The Polish forces aided from central Poland, including general Haller’s Blue Army, equipped by the French, relieved the besieged city in May 1919 forcing the UHA to the east.

Despite Entente mediation attempts to cease hostilities and reach a compromise between belligerents, the Polish–Ukrainian War continued until July 1919, at which time the last UHA forces withdrew east of the river Zbruch. The border on the river Zbruch was confirmed at the Treaty of Warsaw, when in April 1920 Field Marshal Pilsudski signed an agreement with Symon Petlura. It was agreed that for military support against the Bolsheviks, the Ukrainian People’s Republic renounced its claims to the territories of Eastern Galicia.

In August 1920, Lwów was attacked by the Red Army under the command of Aleksandr Yegorov and Stalin during the Polish-Soviet War, but the city repelled the attack. For the courage of its inhabitants Lwów was awarded the Virtuti Militari cross by Józef Piłsudski on 22 November 1920. Polish sovereignty over Lwów was internationally recognised, when the Council of Ambassadors ultimately approved it in March 1923.

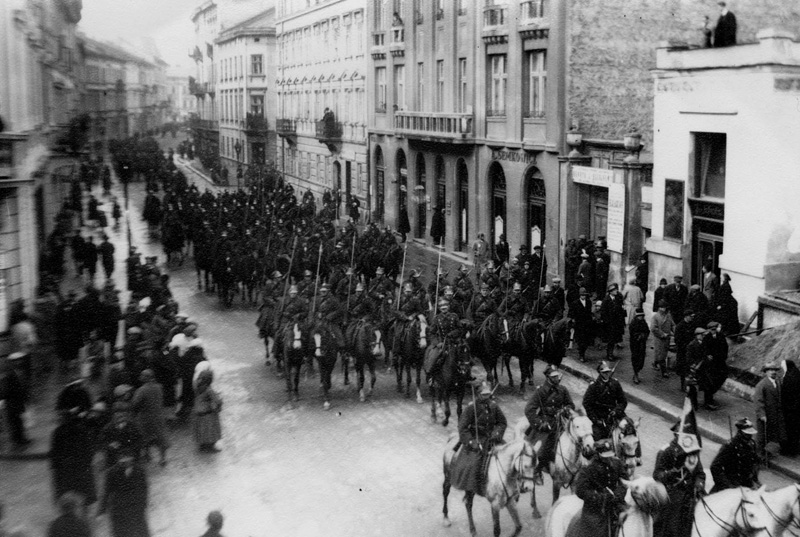

Interbellum

During the interbellum, Lviv held the rank of Poland’s third most populous city (after Warsaw and Łódź) and it became the seat of the Lwów Voivodeship after Warsaw. It was the second most important cultural and academic centre of interwar Poland. For example in 1920, professor Rudolf Weigl of the Lwów University discovered the vaccine against typhus. Furthermore, Lviv’s geographic location gave it an important role in stimulating international trade and fostering the city’s and Poland’s economic development. The major trade fair called ‘Targi Wschodnie’ was established in 1921. In the academic year 1937–38 there were 9,100 students attending five higher education facilities, including the renowned university and institute of technology.

While about two-thirds of the city’s inhabitants were Poles, some of who spoke the characteristic Lwów dialect, the eastern part of the Lwów Voivodeship had a relative Ukrainian majority in most of its rural areas. Although Polish authorities obliged themselves internationally to provide Eastern Galicia with autonomy (including creation of a separate Ukrainian university in Lviv) and even though in September 1922 adequate Polish Sejm’s Bill was enacted, it was not fulfilled. Instead, the Polish government closed down many Ukrainian schools, that had previously flourished during Austrian rule, and closed down every Ukrainian university department at the University of Lviv with the exception of one. Pre-war Lviv also had a large and thriving Jewish community, which constituted about a quarter of the population.

Unlike in Austrian times, when the size and amount of public parades or other cultural expressions corresponded to each cultural group’s relative population, the Polish government emphasized the Polish nature of the city and limited public displays of Jewish and Ukrainian culture. Military parades and commemorations of battles at particular streets within the city, all celebrating the Polish forces who fought against the Ukrainians in 1918, became frequent. And in the 1930s, a vast memorial monument and burial ground of Polish soldiers from that conflict was built in the city’s Lychakiv Cemetery. The Polish government fostered the idea of Lviv as an eastern Polish outpost standing strong against eastern 'hordes'.

World War II and Soviet occupation

Following the signing of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, Germany invaded Poland on September 1, 1939. By the 14th of September, Lviv was completely encircled by German units. Subsequently, the Soviets invaded Poland on September 17. The Soviet Union annexed the eastern part of Second Polish Republic, including the city of Lviv which capitulated to the Red Army on September 22, 1939. The city (Lvov in Russian) became the capital of the newly formed Lviv Oblast. The Soviets opened many Ukrainian-language schools that had been closed by the Polish government and Ukrainian was reintroduced at the University of Lviv, where the Polish government had banned it during the interwar years. It became thoroughly Ukrainized and renamed after Ukrainian writer Ivan Franko. The Soviets also started repressions against local Poles and Ukrainians, deporting many of the citizens to the Asiatic part of the USSR or to gulags.

German occupation

On the 22nd of June 1941, Nazi Germany and several of its allies invaded the USSR. In the initial stage of Operation Barbarossa (30 June 1941), Lviv was taken by the Germans. The evacuating Soviets killed most of the prison population. The arriving Wehrmacht forces easily discovered evidence of Soviet mass murders in the city, committed by the NKVD and NKGB. Ukrainian nationalists, organized as a militia, and the civilian population were allowed to take revenge on the “Jews and Bolsheviks”. They indulged in several mass killings in Lviv and the surrounding region, resulting in the deaths of an estimated number between 4,000 and 10,000 Jews. In Lviv on the 30th of June 1941, Yaroslav Stetsko proclaimed the Government of an independent Ukrainian state, allied with Nazi Germany. This was done without pre-approval from the Germans and after September 15, 1941 the organisers were arrested.

The Sikorski–Mayski Agreement, signed in London on July 30, 1941 between Polish government-in-exile and USSR’s government, invalidated the September 1939 Soviet-German partition of Poland, as the Soviets declared it null and void. Meanwhile, at the start of August 1941, German-occupied Eastern Galicia was incorporated into the General Government as ‘Distrikt Galizien’ with Lviv as the district’s capital. German policy towards the Polish population in this area was as harsh as in the rest of the General Government. Germans, during the occupation of the city, committed numerous atrocities including the killing of Polish university professors in 1941. German Nazis viewed the Ukrainian Galicians, former inhabitants of Austrian Crown Land, as to some point more aryanised and civilised than the Ukrainian population living in the territories belonging to the USSR before 1939. As a result, they escaped the full extent of German acts in comparison to Ukrainians who lived to the east in German-occupied Soviet Ukraine, which was turned into the ‘Reichskommissariat Ukraine’.

According to the Third Reich’s racial policies, local Jews became the main target of German repressions in the region. Following German occupation, the Jewish population was concentrated in the Lwów Ghetto established in the city’s Zamarstynów (today Zamarstyniv) district. The Janowska concentration camp was also set up. There were 75,316 Yiddish speaking inhabitants in 1931, but by 1941 approximately 100,000 Jews were living in Lviv. The majority of these Jews were either killed within the city or deported to the Belzec extermination camp. In the summer of 1943, on orders of Heinrich Himmler, SS-Standartenführer Paul Blobel was tasked with the destruction of any evidence of Nazi mass murders in the Lviv area.

On 15 June, Blobel, using forced labourers from Janowska, dug up a number of mass graves and incinerated the remains. Later, on the 19th of November 1943, inmates at Janowska staged an uprising and attempted a mass escape. A few succeeded, but most were recaptured and killed. The SS staff and their local auxiliaries, at the time of the Janowska camp’s liquidation, murdered at least 6,000 more inmates, as well as Jews in other forced labour camps in Galicia. By the end of the war, the Jewish population of the city was virtually eliminated, with only around 200 to 800 survivors remaining.

Soviet re-occupation

After the successful Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive of 22–24 July 1944, the Soviet 3rd Tank Army recaptured Lviv on 27 July 1944, with cooperation from the local Armia Krajowa resistance. Soon after, the local commanders of the Polish AK were invited to a meeting with the commanders of the Red Army, where they were arrested by the NKVD. In January 1945, the local NKVD also arrested many Poles in Lviv (which, according to Soviet sources, still had a clear Polish majority of 66.7% on 1 October 1944) to encourage their emigration from their city. Those arrested were released after they signed papers agreeing to move to Poland, whose postwar borders were moved westwards according to the Yalta conference settlements, leaving Lviv within the borders of the Soviet Union. On the 16th of August 1945, a border agreement between the government of the Soviet Union and the Provisional Government of National Unity, installed by the Soviets, was signed in Moscow. In that treaty, Poland formally ceded its pre-war eastern part to the Soviet Union, agreeing to the Polish-Soviet border being drawn according to the so-called Curzon Line. Consequently, the agreement was ratified on the 5th of February 1946.

Soviet Union

In February 1946, Lviv became a part of the Soviet Union. It is estimated that from 100,000 to 140,000 Poles were resettled out of the city into the so-called Recovered Territories, as a part of postwar population transfers, many of them to the area of newly acquired Wrocław, formerly the German city of Breslau. Little remains of Polish culture in Lviv, except for the Italian-influenced architecture. The Polish history of Lviv is still well remembered in Poland and those Poles who stayed in Lviv, have formed their own organisation, the Association of Polish Culture of the Lviv Land.

Expulsion of the Polish population, together with migration from Ukrainian-speaking rural areas around the city and from other parts of the Soviet Union, altered the ethnic composition of the city. Immigration from Russia and Russian-speaking regions of Eastern Ukraine was encouraged. Despite this, Lviv remained a major centre of dissident movement in Ukraine and played a key role in Ukraine’s independence in 1991.

In the 1950s and 1960s the city significantly expanded both in population and size mostly due to the city’s rapidly growing industrial base. Due to the fight of SMERSH with the guerrilla formations of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army, the city obtained the negative nickname of ‘Banderstadt’ as ‘the City of Stepan Bandera’. The German suffix for city, ‘stadt’, was added instead of the Russian ‘grad’ to imply collaboration with Nazi Germany. Over the years the residents found this so ridiculous, that even people not familiar with Bandera accepted it as a sarcasm in reference to the Soviet perception of western Ukraine. In the period of liberalisation from the Soviet system during the 1980s, the city became the centre of political movements advocating Ukrainian independence from the USSR. By the time of the fall of the Soviet Union, the name became a proud mark for the Lviv natives, culminating in the creation of a local rock band under the name ‘Khloptsi iz Bandershtadtu’ (Boys from Banderstadt).

Independent Ukraine

Citizens of Lviv strongly supported Viktor Yushchenko during the 2004 Ukrainian presidential election and played a key role in the Orange Revolution. Hundreds of thousands of people would gather in freezing temperatures to demonstrate for the Orange camp. Acts of civil disobedience forced the head of the local police to resign and the local assembly issued a resolution refusing to accept the fraudulent first official results. Lviv remains today one of the main centres of Ukrainian culture and the origin of much of the nation’s political class.

In support of the Euromaidan movement, Lviv’s executive committee declared itself independent of the rule of President Viktor Yanukovych on 19 February 2014.

(…)

(source: Wikipedia)

VIDEOS OF LVIV

"Our Beautiful City"

"Little Paris (in english)"

Lviv from the air

Christmas in Lviv

Lviv Ukraine

BANDS AND SINGERS

Okean Elzy

Jamala

The Hardkiss

Tina Karol

Christina Solovy

Piccardysky Tertsiya

Ruslana

Skryabin

Alyosha

Olexander Ponomarev

Zlata Ognevich

Onuka

Antityla

Loboda

Irina Dumanskaya

Irina Fedishin

Vivienne Mort

Krykhitka Tsakhes

S.K.A.Y.

Druha Rika

Boombox

Buv'ye

Lama

Platch Yeremy

Voply Vidoplasova

T.N.M.K.

Tartak

Noomer 482

Braty Hadukyny

O. Torvald

Bahroma

Epolets

Haidamaky

TIK

Ani Lorak