The first centuries

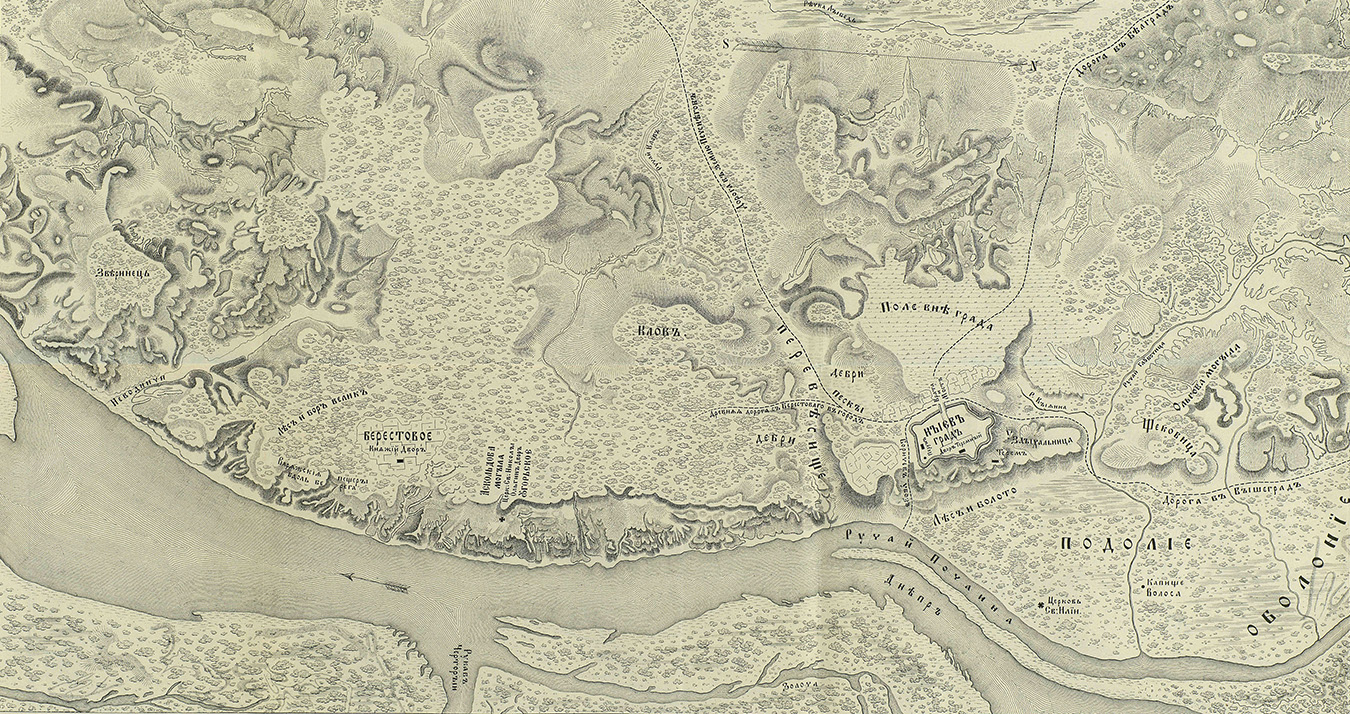

The capital of Ukraine, Kyiv, was founded by the three brothers Kyi, Shek and Khoryv, and their sister Lybed in the late 5th century (482 AD). They were of the Polian people - a group of Slavicized tribes with Iranian origins (not to be confused with the unrelated West-Polian tribe, who are the ancestors of modern day Poles). The city was named after the eldest brother Kyi. Kyiv means 'the city of Kyi'.

In the 8th century Kyiv came under control of the Khazar kaganate and the Polians (and the Siverianians as well) had to pay tribute to the Khazars.

Varangians and Kyivan Rus’

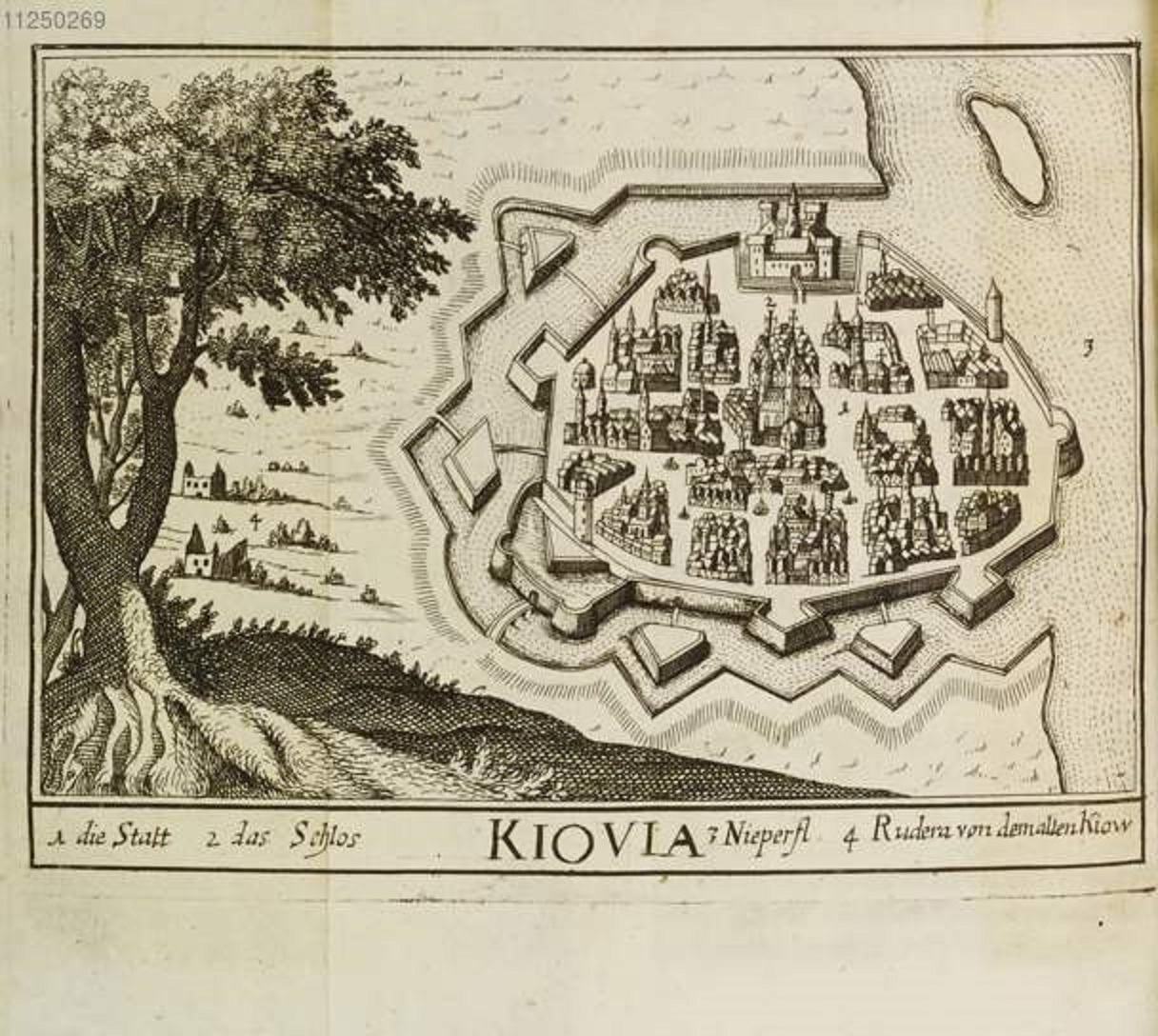

In the 9th century, sailing with their fleet southwards from Novgorod - where Rurik the Varangian (Viking) ruled the Slavic tribes - to Constantinopel, Rurik's men Askold and Dir found 'a small city on a hill' called Kyiv. They took the city and its surroundings from the Khazars, invited more Varangians to come and live there and established their dominion over the tribes in the region.

After Rurik's death (879 AD), his kinsman prince Oleg took Rurik's son Igor to Kyiv to rule the Slavs from there and he called Kyiv 'the mother of all Rus' cities'. This is considered to be the birth of Kyivan Rus'.

Why Rus'? A theory is that the name Rus' comes from the Finnish word for Swedes, Ruotsi, which is derived from an Old Nordic term for 'the men who row’.

Prince Oleg ruled from 882-912. Igor then ruled from 912 until 945. After Igor had been killed by Derevlianians while collecting tributes for a second time in one month, his wife Saint Olga of Kyiv reigned from 945 till 962. Her son Sviatoslav I the Brave ruled a decade, from 962 - 972. He united all the Rus’ principalities under the Kyiv throne after having defeated the Khazar kaganate. His son Yaropolk I sat on the throne from 972-980.

Prosperity and downfall

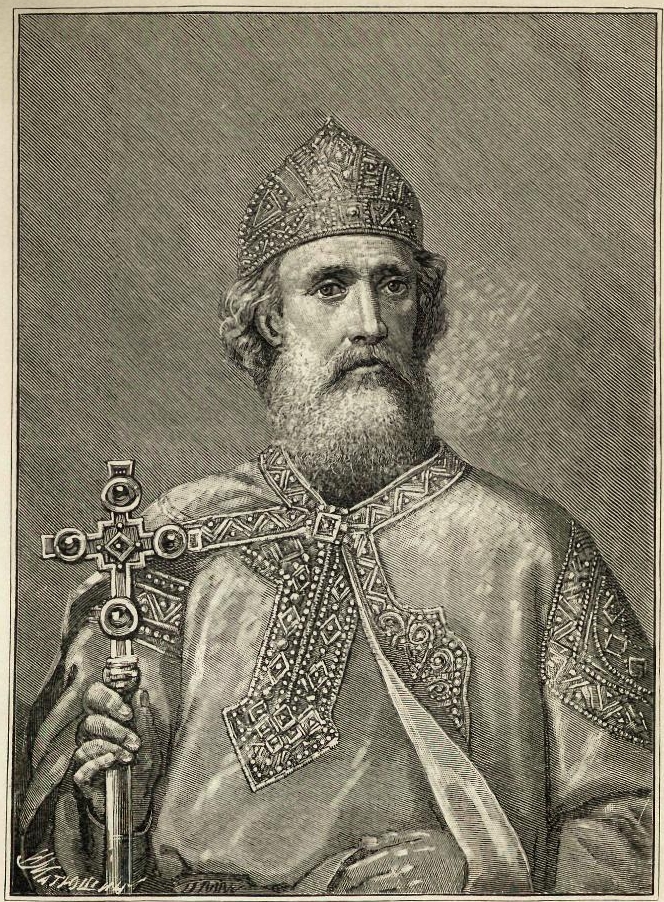

Kyiv's development accelerated during the reign of Grand Duke Vladimir the Great (980-1015). In 988 Vladimir established Orthodox Christianity as the official religion of the realm in order to strengthen the power of Kyiv on the broader international stage. In that period of time the first stone temple, the Desyatinnaya church, was constructed.

During the 11th and 12th centuries Kyiv Rus' reached its greatest period of ascendancy. By the 11th century Kyiv was one of the largest centers of civilization in the Eastern christian world. At that time, there were about 400 churches, 8 markets and more than 50,000 inhabitants in Kyiv. For comparison, at the same time the population of London, Hamburg and Gdansk was about 20,000.

When Vladimir Monomakh died in 1152, the mighty Kyivan Rus' began to decay. In autumn of 1240, the Tatar-Mongols headed by Batu-khan, captured Kyiv after a series of long and bloody battles. Kyiv fell into a prolonged period of decline. The Tartar-Mongols ruled for almost a century.

Poland and Lithuania

In the 14th century Kyiv began to revive again. But in 1362 Great Duke of Lithuania captured the city. During the period between 1362 and 1471, Kyiv was ruled by Lithuanian princes from different families. By order of Casimir Jagiellon, the Principality of Kyiv was abolished and the Kyiv Voivodship was established in 1471.

The city was frequently attacked by Crimean Tatars and in 1482 was destroyed again. In 1494 Kyiv was granted Magdeburg rights and gradually increased its autonomy in a series of acts of Lithuanian Grand Dukes and Polish Kings, finalized by a charter granted by Sigismund I the Old in 1516.

In 1569, under the Union of Lublin that formed the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, Kyiv and other Ukrainian territories were transferred to the Crown of the Kingdom of Poland. The city became the capital of the Kyiv Voivodeship. Its role of Orthodox center strengthened due to expansion of Roman Catholicism under Polish rule.

In 1632, Peter Mogila, the Orthodox Metropolitan of Kyiv and Galicia, established the Kyiv Mogila Academy, an educational institution aimed to preserve and develop Ukrainian culture and Orthodox faith despite Polish Catholic oppression. Although ruled by the church, the academy provided students with educational standards close to universities of Western Europe (including multilingual training) and became the foremost educational center, both religious and secular.

Bogdan Khmelnitsky

The long road to Ukraine's independence began with Cossack military campaigns. In 1648-1654, Cossack armies headed by Hetman Bogdan Khmelnitsky, Ukraine's Cossack leader, waged several wars to liberate Ukraine. In 1648, when the Ukrainian Cossacks rose against Poland, Kyiv became for a brief period the center of the Ukrainian State. But soon, confronted by the armies of Polish and Lithuanian feudal lords, Bogdan Khmelnitsky sought the help of the Russian Tsar with the Treaty of Pereyaslavl.

On January 31, 1667, the Truce of Andrusovo was concluded, in which the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth ceded Smolensk, Severia and Chernigov, and, on paper only for a period of two years, the city of Kyiv to the Tsardom of Russia. The Eternal Peace of 1686 acknowledged the status quo and put Kyiv under the control of Russia for the centuries to come. Kyiv slowly lost its autonomy, which was finally abolished in 1775 by the Empress Catherine the Great.

Despite the long period of domination by the Russian Empire, Ukraine managed to preserve and enjoy some of its rich political, economic, cultural, and religious achievements in the 17th and 18th century.

Polish influence

After Kyiv and the surrounding area were no longer part of Poland, Poles did continue to play an important role. In 1812 there were over 43,000 Polish noblemen in the Kyiv province, compared to only 1,000 ‘Russian’ nobles. Until the mid-18th century, Kyiv was Polish in culture, even though Poles made up no more than ten percent of the population and 25% of the voters. During the 1830s Polish was the language of the educational system.

The cancellation of Kyiv's autonomy by the Russian government and its placement under the rule of bureaucrats appointed from St. Petersburg was largely motivated by fear of a Polish insurrection in the city. Warsaw factories and fine Warsaw shops had branches in Kyiv. Józef Zawadzki, founder of Kyiv's stock exchange, served as the city's mayor in the 1890s. Kyivan Poles tended to be friendly towards the Ukrainian national movement in the city, and some took part in Ukrainian organizations. Indeed, many of the poorer Polish nobles became Ukrainianized in language and culture and these Ukrainians of Polish descent constituted an important element of the growing Ukrainian national movement.

Kyiv served as a meeting point where such activists came together with the pro-Ukrainian descendents of Cossack officers from the left bank. Many of them would leave the city for the surrounding countryside in order to try to spread Ukrainian ideas among the peasants.

Russification

Following the gradual loss of Ukraine's autonomy and suppression of the local Ukrainian and Polish cultures, Kyiv experienced growing Russification in the 19th century by means of Russian migration, administrative actions (such as the Valuev Circular of 1863), and social modernization. At the beginning of the 20th century, the city was dominated by Russian-speaking population.

During the Russian industrial revolution in the late 19th century, Kyiv became an important trade and transportation center of the Russian Empire, specializing in sugar and grain export by railroad and on the Dnieper river. By 1900, the city had also become a significant industrial center, having a population of 250,000.

The development of aviation became another notable mark of distinction of early 1900s Kyiv. Prominent aviation figures of that period include Kyivites Pyotr Nesterov (aerobatics pioneer) and Igor Sikorsky. The world's first helicopter was built and tested in Kyiv by Sikorsky. In 1892 the first electric tram line of the Russian Empire was established in the Principality of Kyiv.

Independence and occupation

In 1917 the Central Rada (Tsentralna Rada), a Ukrainian self-governing body headed by the historian Mykhailo Hrushevsky, was established in the city. Later that year, Ukrainian autonomy was declared. On 7 November 1917 it was transformed into an independent Ukrainian People's Republic with Kyiv as the capital. During this short period of independence, Kyiv experienced rapid growth of its cultural and political status.

After the January Uprising on January 29, 1918 was extinguished, Bolshevik troops took the city in the Battle of Kyiv, but established Kharkiv as the capital of the Soviets of the Ukraine. In March Kyiv was occupied by the Germans.

When the German troops withdrew after the war, an independent Ukraine was declared in Kyiv under Symon Petliura. It was then briefly occupied by the White armies before the Soviets once more took control in 1920. In May 1920, during the Russo-Polish War, Kyiv was briefly captured by the Polish Army but they were driven out by the Red Army.

After the Ukrainian SSR was formed in 1922, Kharkiv was declared its capital. Kyiv continued to grow and in 1925 the first public buses drove through the streets of Kyiv, and ten years later the first trolleybusses were introduced. In 1927, the suburban areas of Darnytsia, Lanky, Chokolivka and Nikolska slobidka were included in the city. In 1932, Kyiv became the administrative center of newly created Kyiv Oblast.

Russian terror

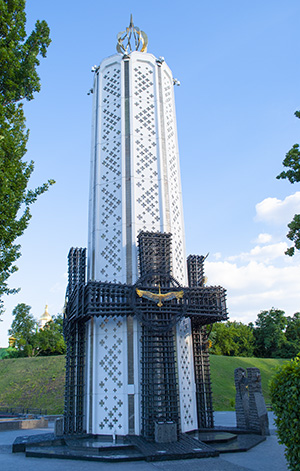

In 1932-1933, the Holodomor (derived from ‘Moryty Holodom’ (‘to kill with starvation’)) was a famine ordered by Stalin. Millions of Ukrainians starved to death. It is also known as the ‘Terror-Famine’ and ‘Famine-Genocide in Ukraine’, and sometimes it is referred to as ‘the Great Famine’ or ‘The Ukrainian Genocide of 1932–33’.

According to higher estimates, up to 12 million ethnic Ukrainians perished as a result of the famine. A joint statement of the U.N., signed by 25 countries in 2003, declared that 7-10 million Ukrainians perished. According to the findings of the Court of Appeal of Kyiv in 2010, the demographic losses due to the famine amounted to 10 million.

Since 2006, the Holodomor has been recognized by Ukraine and 15 other countries as genocide of the Ukrainian people by the Soviet government.

World War II

The First Battle of Kyiv (1941) was the German name for the operation that resulted in a very large encirclement of Soviet troops in the vicinity of Kyiv during World War II. This encirclement is considered to be the largest encirclement in history of warfare (by number of troops). The operation ran from 7 August to 26 September 1941 as part of Operation Barbarossa. In Soviet military history, it is referred to as the Kyiv Strategic Defensive Operation, with somewhat different dating of 7 July – 26 September 1941.

Much of the Southwestern Front of the Red Army (Mikhail Kirponos) was encircled, but small groups of Red Army troops managed to escape. Kirponos was trapped behind German lines and killed while trying to break out.

The battle was an unprecedented defeat for the Red Army, exceeding even the Battle of Białystok–Minsk of June–July 1941. The Southwestern Front suffered 700,544 casualties. The 5th, 21st, 26th, 37th and the 38th armies, consisting of 43 divisions, were almost annihilated and the 40th Army suffered heavy losses.

The Second Battle of Kyiv involved three strategic operations by the Soviet Red Army, and one operational counterattack by the Wehrmacht which took place between 3 October and 22 December 1943. Following the Battle of Kursk, the Red Army launched Belgorod-Khar'kov Offensive Operation, pushing Erich von Manstein's Army Group South back towards the Dnieper River. The Soviet high command ordered the Central Front and the Voronezh Front to force crossings of the Dnieper. When this was unsuccessful in October, the effort was handed over to the 1st Ukrainian Front, with some support from the 2nd Ukrainian Front. The 1st Ukrainian Front, commanded by Nikolai Vatutin, was able to secure bridgeheads north and south of Kyiv.

First attempt

In October 1943, several of Vatutin's armies were having serious trouble trying to break out of the rugged terrain of the Bukrin bend, the southern bridgehead. The 24th Panzer Corps of Walther Nehring, in an effective defensive position, had the opposing Soviet forces squeezed in. As a result, Vatutin decided to concentrate his strength at the northern bridgehead at Lyutezh. The 3rd Guards Tank Army, commanded by Pavel Rybalko, moved northwards toward the Lyutezh bridgehead under cover of darkness and diversionary attacks out of the Bukrin bend. Masses of artillery were shifted northwards, but the movements went unnoticed by the Germans.

Initial stage of second attempt

Early on the morning of 3 November 1943, the 4th Panzer Army was subjected to a massive Soviet bombardment. The German forces screening the bridgehead were defeated, and Kyiv was quickly captured. The 1st Ukrainian Front's objective was to drive quickly westward in order to take the towns of Zhitomir, Korosten, Berdichev and Fastiv, and to cut the rail link to Army Group Center; this would be the first step towards the encirclement of Army Group South.

The plan went very well for Vatutin; Manstein, however, became worried. As Rybalko's tanks moved through the streets of Kyiv on 5 November, Manstein pleaded with Adolf Hitler to release the 48th and 40th Panzer Corps in order to have sufficient forces to retake Kyiv. The 48th Panzer Corps was committed to Manstein. Hitler refused to divert the 40th Panzer Corps, and replaced Hoth with Erhard Raus, who was ordered to blunt the Soviet attack and secure Army Group South's northern flank and communications with Army Group North. A number of sources give 6 November as the date for the fall of Kyiv. The 1st Czechoslovak Independent Brigade seems to have started the assault earlier, at 12.30 on 5 November, reaching the Dniepr at 02.00 on the 6th, after sweeping through the western suburbs of the city and were the first unit in the city center, with Kyiv finally being captured at 06.50 on the 6th.

Raus counterattacks

Raus was in difficulty with his units suffering heavy casualties in the initial stages of Vatutin's offensive. The 4th Panzer Army was reinforced, especially with artillery and rockets. The German divisions were bolstered on 7 November by the arrival of the newly formed 25th Panzer Division commanded by General der Panzertruppen Georg Jauer. Its drive on Fastov was halted by the 7th Guards Tank Corps. Rybalko was soon just 40 mi (64 km) from Berdichev. Zhitomir was taken by the 38th Army; the 60th Army was at the gates of Korosten; 40th Army was moving south from Kyiv. The only respite for the Germans came when the 27th Army exhausted itself and went over to the defensive in the Bukrin bend.

Panzer IVs in Zhitomir, November 1943

The 4th Panzer Army was in deep trouble. However, the situation changed with the arrival of Hermann Balck's XLVIII Panzer Corps, comprising the 1st SS Division, 1st Panzer Division and 7th Panzer Division. Balck drove his forces north to Brusyliv and then west to retake Zhitomir. Rybalko sent the 7th Guards Tank Corps to counter the German assault. A huge tank battle ensued, which continued until the latter part of November, when the autumn mud halted all operations. Both sides had suffered heavy losses. The casualty ratio was fairly balanced, though the Soviets lost slightly more than the Germans. With the recapture of Zhitomir and Korosten the 4th Panzer had gained some breathing room. With Vatutin halted, Stavka released substantial reserves to his First Ukrainian Front to regain momentum.

Final stage of second attempt

By 5 December, the mud had frozen in the Soviet winter. 48th Panzer Corps conducted a wide sweeping attack north of Zhitomir. Catching the Soviets by surprise, the Germans sought to trap the Soviet 60th Army, and the 13th Corps. Reinforced with the 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division, the Germans drove eastward, putting the Soviets on the defensive. With Fastiv also being threatened, the 60th Army withdrew from Korosten.

Vatutin was forced to ask Stavka for more reserves, and was granted 1st Tank Army and 18th Army. These new units, along with additional Corps from other sectors, were hastily rushed westward. Thus, the Soviets stopped the German advance, went back on the offensive, and retook Brusilov. Both sides were exhausted by late December and the battle for Kyiv was over.

Second half of the 20th century

Post-wartime in Kyiv was a period of rapid socio-economic growth and political pacification. The arms race of the Cold War caused the establishment of a powerful technological complex in the city (both R&D and production), specializing in aerospace, microelectronics and precision optics. Dozens of industrial companies were created employing highly skilled personnel. Sciences and technology became the main issues of Kyiv's intellectual life. Dozens of research institutes in various fields formed the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR.

Kyiv also became an important military center of the Soviet Union. More than a dozen military schools and academies were established here, also specializing in high-tech warfare (see also Soviet education). This created a labor force demand which fed migration from rural areas of both Ukraine and Russia. Large suburbs and an extensive transportation infrastructure were built to accommodate the growing population. However, many rural-type buildings and groves have survived on the city's hills, creating Kyiv's image as one of the world's greenest cities.

The city grew tremendously from the 1950s through to the 1980s. Some significant urban achievements of this period include establishment of the Metro, building new river bridges (connecting the old city with Left Bank suburbs), and Boryspil Airport (the city's second, and later international airport).

More Russification

Systematic oppression of pro-Ukrainian intellectuals, conveniently and uniformly dubbed as "nationalists", was carried under the propaganda campaign against Ukrainian nationalism threatening the Soviet way of life. In cultural sense it marked a new wave of Russification in the 1970s, when universities and research facilities were gradually and secretly discouraged from using Ukrainian. Switching to Russian, as well as choosing to send children to Russian schools was expedient for educational and career advancement. Thus the city underwent another cycle of gradual Russification.

Every attempt to dispute Soviet rule was harshly oppressed, especially concerning democracy, Ukrainian SSR's self-government, and ethnic-religious problems. Campaigns against 'Ukrainian bourgeois nationalism' and 'Western influence' in Kyiv's educational and scientific institutions were mounted repeatedly. Due to limited career prospects in Kyiv, Moscow became a preferable life destination for many Kyivans (and Ukrainians as a whole), especially for artists and other creative intellectuals. Dozens of show-business celebrities in modern Russia were born in Kyiv.

The Chernobyl nuclear disaster in 1986 affected city life tremendously, both environmentally and socio-politically. Some areas of the city have been polluted by radioactive dust. However, Kyivans were neither informed about the actual threat of the accident, nor recognized as its victims. Moreover, on May 1, 1986 (a few days after the accident), local CPSU leaders ordered Kyivans (including hundreds of children) to take part in a mass civil parade in the city's center 'to prevent panic'. Later, thousands of refugees from accident zone were resettled in Kyiv.

Independence

On January 21 1990, over 300,000 Ukrainians organised a human chain for Ukrainian independence between Kyiv and Lviv, in memory of the 1919 unification of the Ukrainian People's Republic and the West Ukrainian National Republic. Citizens took to the streets and highways, forming live chains by holding hands in support of unity.

Ukraine officially declared itself an independent state on August 24, 1991, when the communist Supreme Soviet (parliament) of Ukraine proclaimed that Ukraine will no longer follow the laws of USSR and only the laws of the Ukrainian SSR, de facto declaring Ukraine's independence.

On December 1, Ukrainian voters overwhelmingly approved a referendum formalising independence from the Soviet Union. Over 90% of Ukrainian citizens voted for independence, with majorities in every region, including 56% in Crimea, which had a 75% ethnic Russian population.

Poland and Canada were the first countries to recognize Ukraine's independence (both) on 2 December 1991.

First presidents

The history of Ukraine between 1991 and 2004 was marked by the presidencies of Leonid Kravchuk and Leonid Kuchma. This was a time of transition for Ukraine. While it had attained nominal independence from Russia, its presidents maintained close ties with their neighbours.

On June 1, 1996, Ukraine became a non-nuclear nation when it sent the last of its 1,900 strategic nuclear warheads, which it had inherited from the Soviet Union, to Russia for dismantling. Ukraine had committed to this by signing the Budapest Memorandum on Security Assurances in January 1994. The memorandum was originally signed by three nuclear powers, the Russian Federation, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. The memorandum included security assurances against threats or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of Ukraine, Belarus and Kazakhstan.

The country adopted its constitution on June 28, 1996.

The Cassette Scandal of 2000 was one of the turning points in Ukraine's modern history. The Cassette Scandal, also known as Tape-gate or Kuchma-gate, was so named because of tape recordings of Ukrainian President Leonid Kuchma ordering the kidnap of a journalist. It was one of the main political events in Ukraine's post-independence history. It has dramatically affected the country's domestic and foreign policy, changing Ukraine's orientation at the time from Russia to the West and damaging Kuchma's career.

On 28 November 2000 in Kyiv, politician Oleksandr Moroz publicly accused President Kuchma of involvement in the abduction of journalist Georgiy Gongadze and numerous other crimes. Moroz named Kuchma's former bodyguard, Major Mykola Melnychenko, as the source. He also played selected recordings of the President's secret conversations for journalists, supposedly confirming Kuchma's order to kidnap Gongadze. That and hundreds of other conversations were later published worldwide by Melnychenko.

Orange revolution

In 2004, Leonid Kuchma announced that he would not run for re-election. Two major candidates emerged in the 2004 presidential election. Viktor Yanukovych, supported by Kuchma and by the Russian Federation, wanted closer ties with Russia. The main opposition candidate, Viktor Yushchenko, called for Ukraine to turn its attention westward and eventually join the EU.

In the runoff election, Yanukovych officially won by a narrow margin, but Yushchenko and his supporters cried foul, alleging that vote rigging and intimidation cost him many votes, especially in eastern Ukraine. A political crisis erupted after the opposition started massive street protests in Kyiv and other cities, and the Supreme Court of Ukraine ordered the election results null and void. A second runoff found Viktor Yushchenko the winner. Five days later, Viktor Yanukovych resigned from office and his cabinet was dismissed on January 5, 2005.

Yanukovich and Euromaidan

When young, Yanukovych was sentenced to 3 years because of theft, looting and vandalism and later had his sentenced doubled. During Victor Yanukovych's presidency, he had been accused of tightening press restrictions and a renewed effort in parliament to limit freedom of assembly. One frequently-cited example of Yanukovych's attempts to centralize power is the arrest of Yulia Tymoshenko in August 2011. Other high-profile political opponents also came under criminal investigation since. On 11 October 2011, a Ukrainian court sentenced Tymoshenko to seven years in prison after she was found guilty of abuse of office when brokering the 2009 gas deal with Russia. The conviction is seen as "justice being applied selectively under political motivation" by the European Union and other international organizations.

In November 2013, President Yanukovych -a puppet of Moscow- did not sign the Ukraine–European Union Association Agreement and instead pursued closer ties with Russia. This move sparked protests on the streets of Kyiv. Protesters set up camps in Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square), and in December 2013 and January 2014 protesters started taking over various government buildings, first in Kyiv and later also in other cities. In Februari 2014, the peaceful protest turned violent and many people got killed. It is still unknown who actually started the shooting, but there are several theories. A theory is that Russian snipers were positioned on rooftops around Independence Square. Andriy Parubiy, former Commandant of Maidan and deputy speaker of the Ukrainian parliament, stated: "I'm certain that the shootings of the 20th (February) were carried out by snipers who arrived from Russia and who were controlled by Russia. The shooters were aiming to orchestrate a bloodbath on Maidan." (Read the full article here on BBC.com)

Following the violence, the Parliament turned against Yanukovych and on February 22 voted to remove him from power, and to free Yulia Tymoshenko from prison. The same day Yanukovych supporter Volodymyr Rybak resigned as speaker of Parliament, and was replaced by Tymoshenko loyalist Oleksandr Turchynov, who was subsequently installed as interim President. Yanukovych fled to Russia and is wanted in Ukraine for the killing of protesters.

Crimea and the Donbass

Russia took advantage of the unstable situation and on the 18th of March 2014 illegally and forcefully took the Ukrainian peninsula of Crimea. Apart from occupying Crimea, Russia actively supported and supplied the separatists in eastern Ukraine (Donbass) and continues to do so, factually waging war with Ukraine. Of course Moscow denied being involved and called it 'a civil war'. In April 2014, separatists self-proclaimed the Donetsk People's Republic and Lugansk People's Republic. They held a referendum on 11 May 2014 and claimed that nearly 90% voted in favour of independence. It is of course not unthinkable that Russia put those separatists there in the first place, to destabilize the region.

Later in April 2014 fighting between the Ukrainian army and volunteer battalions against the forces supporting the Donetsk and Lugansk People's Republics escalated into the War in Donbass. As Russian involvement became more and more clear, Putin stated that "he needed to protect his fellow-Russians in eastern Ukraine", the same excuse Hitler used for the Sudeten Germans in Czechoslovakia in 1938.

Until now, over 6,400 people have lost their lives in this war and according to United Nations figures it led to over half a million people internally displaced within Ukraine and two hundred thousand refugees to flee to neighboring countries.

source: www.Kyiv.info - Wikipedia - ipfs.io

VIDEOS ABOUT KYIV

"Golden Gate"

"Arsenalna subway station"

advertisement

Christmas in Lviv

Lviv Ukraine

advertisement

BANDS AND SINGERS

Okean Elzy

Jamala

The Hardkiss

Tina Karol

Christina Solovy

Piccardysky Tertsiya

advertisement

Ruslana

Skryabin

Alyosha

Olexander Ponomarev

Zlata Ognevich

Onuka

advertisement

Antityla

Loboda

Irina Dumanskaya

Irina Fedishin

Vivienne Mort

Krykhitka Tsakhes

advertisement

S.K.A.Y.

Druha Rika

Boombox

Buv'ye

Lama

Platch Yeremy

advertisement

Voply Vidoplasova

T.N.M.K.

Tartak

Noomer 482

Braty Hadukyny

O. Torvald

advertisement

Bahroma

Epolets

Haidamaky

TIK

Ani Lorak